Having shared my transformative attention restoration theory (ART) experience in the previous Nurture through Nature blog post, I thought it would be helpful to spend some time talking about the concepts associated with attention restoration and the plethora of research that supports its value and importance for each and every one of us. In getting started with writing this blog post and for fun and to satisfy some insatiable personal curiosity, I decided to do a quick literature search through my university’s library of attention restoration theory. I found the following. There are, as of this blog post 103,792 articles, 19,825 book chapters, and 2,122 books that, in some capacity, reference ART. A bulk of the publications are associated with the subject areas of psychology, public health, and nature. A Google Scholar search yielded about 1,640,00 (total) results.

As I described in my last post, the ART was developed by environmental psychologists Stephen and Rachel Kaplan. The premise of ART is that the negative and enduring effects of attentional fatigue from prolonged tasks requiring focused attention can lead to decreased productivity and accuracy, impulsivity, anger, and careless behavior and are best ameliorated though engagement and/or connection with natural settings (Kaplan, 1995; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989). Stephen Kaplan (1995) determined that a space affords attentional restoration if it provides

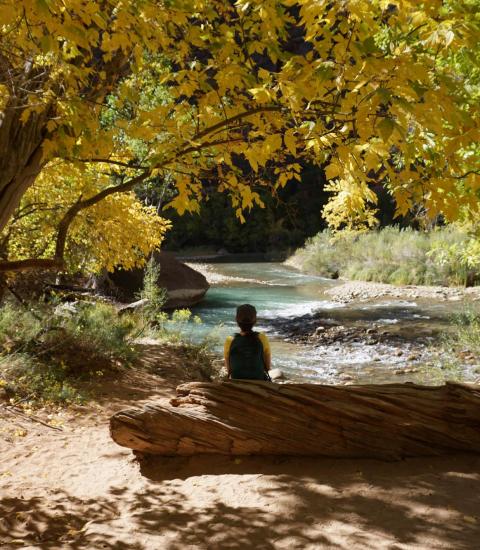

1) fascination- involuntary attention. Typically, soft fascination (i.e. a sunset or view of the ocean) is more restorative than hard fascination (the neon billboards in Time Square in New York City).

2) being away- the conceptualization of being in a new place. A being away experience could be shifting gaze from one window to another or changing body position to watch a bird in flight across a meadow.

3) compatibility- an outdoor environment provides someone with what they want and need. This could be a park with smooth and flat pathways that enable someone to safely walk or the smells of saltwater on a sandy ocean beach.

4) extent- a sense of being in a space that is bigger than it is. Extent can be experienced through near and far views; a garden with lush plants and in the distance, the tall trees.

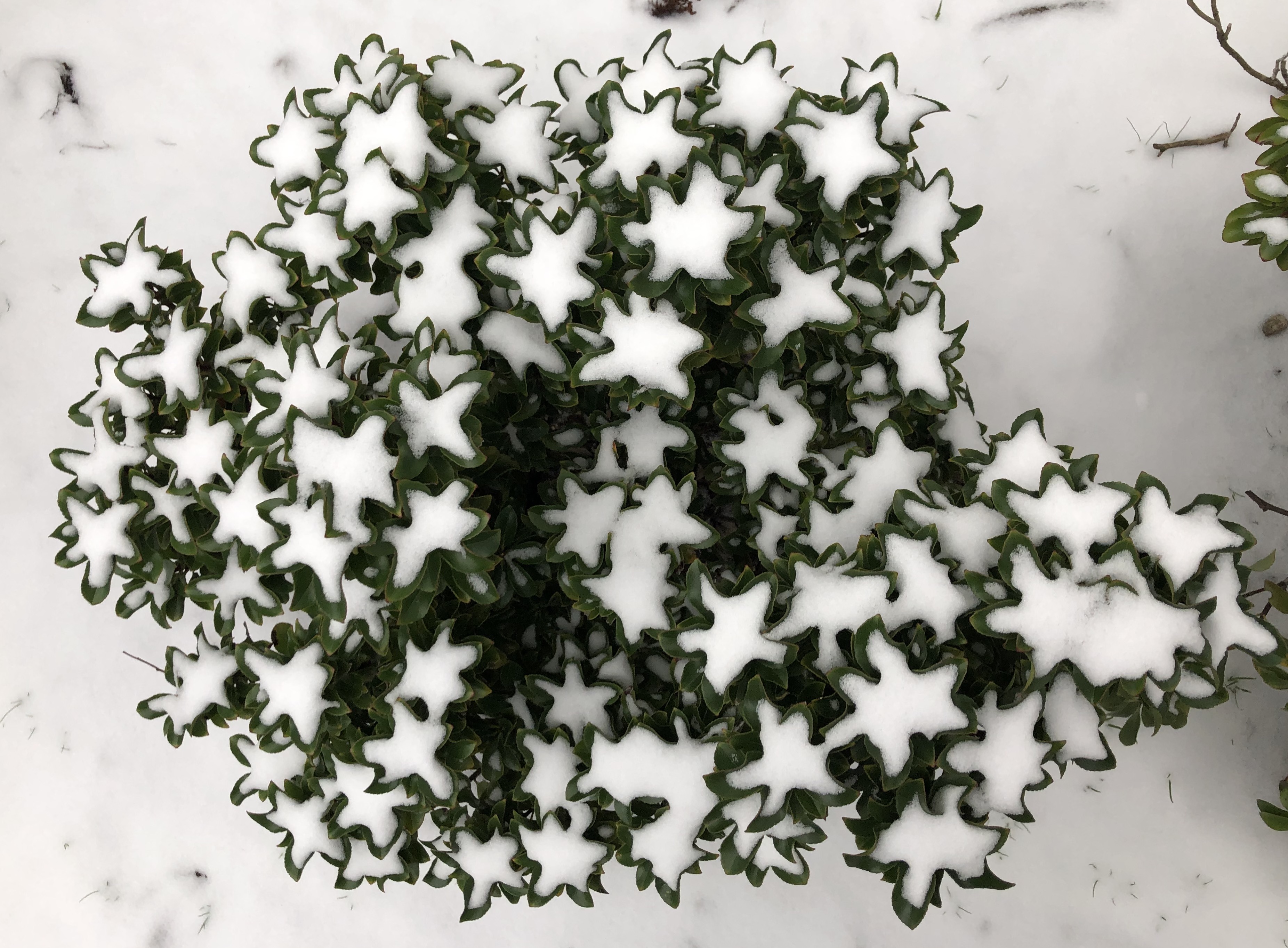

How does all of this resonate with you? I recently participated in a series of user experience workshops for a major tech company. Overwhelmingly and during this period of work at home, the number one strategy the participants used to re-center, re-focus, relieve stress, and to simply take a break was through nature connections; walking, sitting, some gardening, or viewing. When we do return to work (offices), I think that the forward thinking employers are going to recognize the value of nature and contract with designers and planners to make workplace environments more conducive to providing attentional restoration. This environmental ‘upgrade’ could look like courtyard gardens, outdoor meeting rooms, rooftop gardens, or a plethora of indoor nature such as plants, fish tanks, and nature based art to look at and touch.

Before I sign off, I would be remiss if I did not share a few of the many important research findings that support ART. They range from identifying the restorative capacity of 40-second micro breaks on university students who viewed a green meadowlike roof rather versus a concrete one (Lee et al., 2015), to looking at how the restorative capacity of nature and participation in nature based activities can strengthen family interaction (Izenstark & Ebata, 2016) to a systematic review of the literature on ART with regard to association with nature leading to improved sense of mental health and wellbeing (Berto, 2014).

While these three findings are less than a toe dip into what has been and continues to be researched, please feel free to share your most restorative nature experience or ways that you are integrating nature into your life during the Covid-19 pandemic in the comment section. Be well and go outside!

References

Berto, R. (2014). The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: A literature review on restorativeness. Behavioral Sciences, 4(4), 394–409. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs4040394

Lee, K.E., Williams, K.J.H., Sargent, L.D., Williams, N.S.G., & Johnson, K. (2015). 40-second green roof views sustain attention: The role of micro-breaks in attention restoration. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 42, 182-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.04.003

Izenstark, D. & Ebata, A.T. (2016). Theorizing family-based nature activities and family fucntionng: The integration of attention restoration theory with a family routines and rituals perspective. Journal of Family Theory & Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12138

Kaplan, R. & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward and integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15, 169-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2